Eliza Corsey Hopewell.

What we know, what we think we know

Belle Boyd’s life is well-documented. In stark contrast, there is little information available for the enslaved woman, Eliza Corsey Hopewell. Not only are the facts sparse, they are sometimes contradictory. But in 1865, after passage of the Thirteenth Amendment abolishing slavery, Eliza and her family begin to appear in census records. In the 1870 census, the first after the Civil War, we finally have official acknowledgement of Eliza’s existence. Recorded every ten years, these census reports not only document the post-Civil War lives of Eliza and her family, they also shed light on her earlier years.

Date and place of birth

In the 1870 census, Eliza states her age as 36, so she must have been born in 1834, making her ten years older than Belle. Eliza reports her place of birth as being either WV (1870 census) or VA (1880 and 1900 censuses). This confusion stems from the fact that her birthplace was in the part of Virginia that seceded during the Civil War and formed the state of West Virginia. In the 1880 census Eliza states that her parents were also born in Virginia. This is important information because there has been some confusion about where Eliza was born and how she came to live with Belle and her family in Martinsburg. The accepted story is that Eliza ran away from a different family of enslavers in order to live with the Boyds. This raises two questions: “Where was Eliza running from?” and “Why seek protection with the Boyds?”

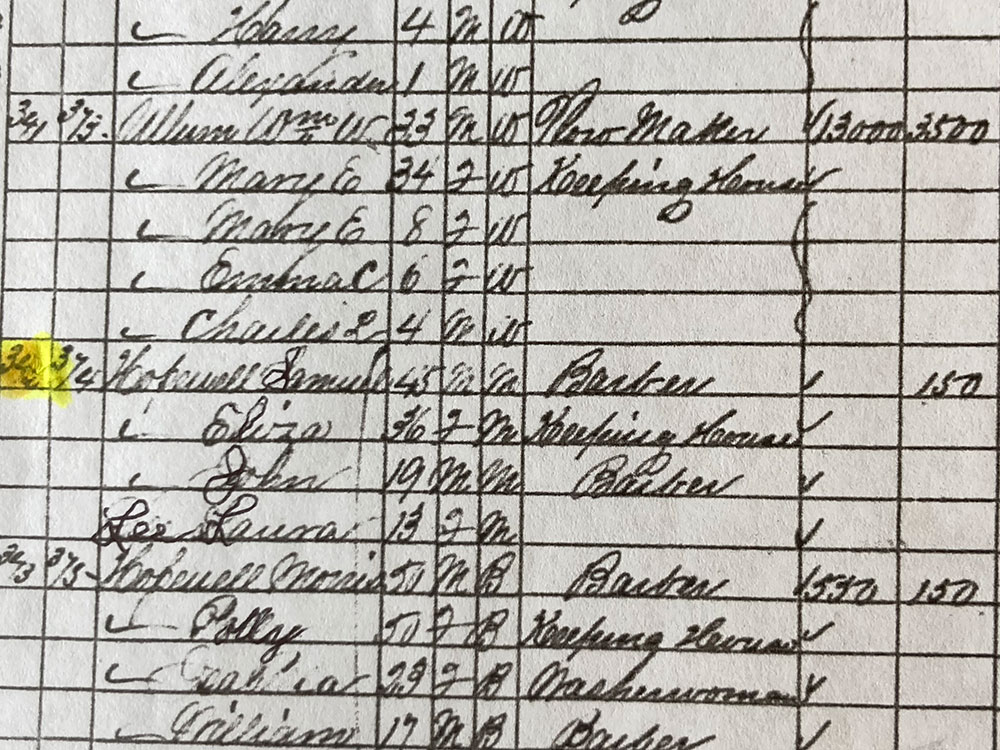

1870 Census record with entry for Hopewell family

Possible escape narratives

In a 1965 letter to a Belle Boyd researcher, one of Eliza’s descendants, Ann Berry, wrote that Eliza escaped from a plantation in the Deep South. This disagrees with Eliza’s own report that she and her parents were born in WV/VA. Another reason for doubt is that Eliza’s grand-daughter gives no information on the name of the plantation, the state where it was located, or any details about Eliza’s hazardous journey North. In her letter Ann Berry mentions Eliza’s Deep South origins and then quickly moves on to the next part of the story, in which her grandmother seeks refuge with the Boyds. But this raises questions too. Why would Eliza stop in Martinsburg? Why not keep going to Pennsylvania (only 27 miles north and a safer haven for those escaping enslavement)? Why would Eliza decide she was safe once she reached the Boyds?

Not to dismiss Eliza’s history as handed down by her own family, but it seems more plausible that rather than escaping from the Deep South, Eliza ran away from somewhere much closer to Martinsburg. This is supported by the census records in which Eliza herself claims that she and her parents were all born in WV/VA.

Most Belle Boyd historians feel comfortable with the version of Eliza’s story that has her escaping from a nearby location. This narrative claims that Eliza ran away from a plantation named Glenburnie, which had originally belonged to Belle’s grandparents and now was owned by Belle’s uncle. According to this version, Eliza heard rumors that she might be “sold south” and took the chance of running away. Glenburnie was where Belle’s grandmother had lived during her marriage and where Belle’s mother grew up, and it was only eight miles from Martinsburg. The short distance would have meant that Eliza’s journey was not particularly dangerous and could have been completed in a single night.

The Boyds would have been frequent visitors to their relatives at nearby Glenburnie. As an enslaved woman working in the “big house” rather than toiling in the fields, Eliza must have known Belle’s mother and grandmother. In fact, Belle’s grandmother was Eliza’s former owner. By seeking refuge with an enslaver from within the family, Eliza may have thought her escape would be viewed less seriously, that the Boyds would allow her to stay, and she could therefore avoid being sold far away from the place and people she knew.

In the end, all we know for certain is that Eliza escaped from a plantation, probably Glenburnie; sought refuge with the Boyds in Martinsburg; and was permitted to remain with the family.

The Glenburnie House

Belle teaching Eliza to read

Another well-known part of Belle’s and Eliza’s story is the claim that Belle taught Eliza to read. There is no real proof of this, but it is definitely part of Belle’s legend. Eliza’s granddaughter Ann Berry reports this as fact.

We do know that Eliza and Belle were in contact until Belle’s death in 1900. To celebrate the birth of Eliza’s first grandson, Belle sent a highchair and a china bowl painted with the letters of the alphabet. The fact that Belle knew about this baby could be evidence that she and Eliza corresponded. However, no letters have survived.

Eliza assisting in Belle’s wartime adventures

In her 1865 memoir, now accepted by Civil War historians as mostly factual, Belle reports Eliza’s assistance in carrying messages to Confederate camps, nursing Confederate soldiers, and burning incriminating papers to help Belle avoid arrest. The big question of course is — Why?

The frustrating answer is that we don’t know, and probably never will. Writers of biographical fiction do lots of research to uncover facts about historical events and the actions of real-life individuals involved in those events. Their next task is to imagine what lies behind those actions. My speculations about what motivated Eliza’s loyalty are at the core of the chapters in the book devoted to her inner thoughts. There’s no way of knowing if my guesses are correct. What we do know for certain is that Eliza helped Belle, and that these two women, who could not have been more different in their lives and circumstances, remained close until Belle’s death three decades later.

Census records – finally some facts

1870 Census close-up for Hopewell family. Note value of Sam’s personal property set at $150.

Once the facts of Eliza’s life become part of the historical record, what can we learn from them? The 1870 census, the first after the Civil War, shows Eliza living in Martinsburg in her own house, along with Sam and their two children — John, aged 19, and Lee Laura, aged 13. Sam’s trade is listed as “Barber”, as is John’s. Eliza’s occupation is listed as “Keeping House”. In the 1880 census, Eliza gives her occupation as “Washerwoman”. Though it is not mentioned in these documents, a newspaper article written at the time of Eliza’s death in 1916 makes reference to her sometimes working as a midwife/assistant to a local doctor.

A dream fulfilled

What else can be learned from these bare facts? The first is that Eliza and her family prospered once they were free persons. With the fruits of their intelligence, competence, energy, and hard work no longer limited by enslavement, their lives improved dramatically. Already in 1870, they were living together as a family, everyone under one roof. For Eliza this must have been the fulfillment of a lifelong dream. Her family united. Every one of them a free person.

The census indicates that their home was rented. However, the census taker estimates the value of Sam Hopewell’s personal goods as $150, a considerable sum at the time. Another indication of the family’s prosperity.

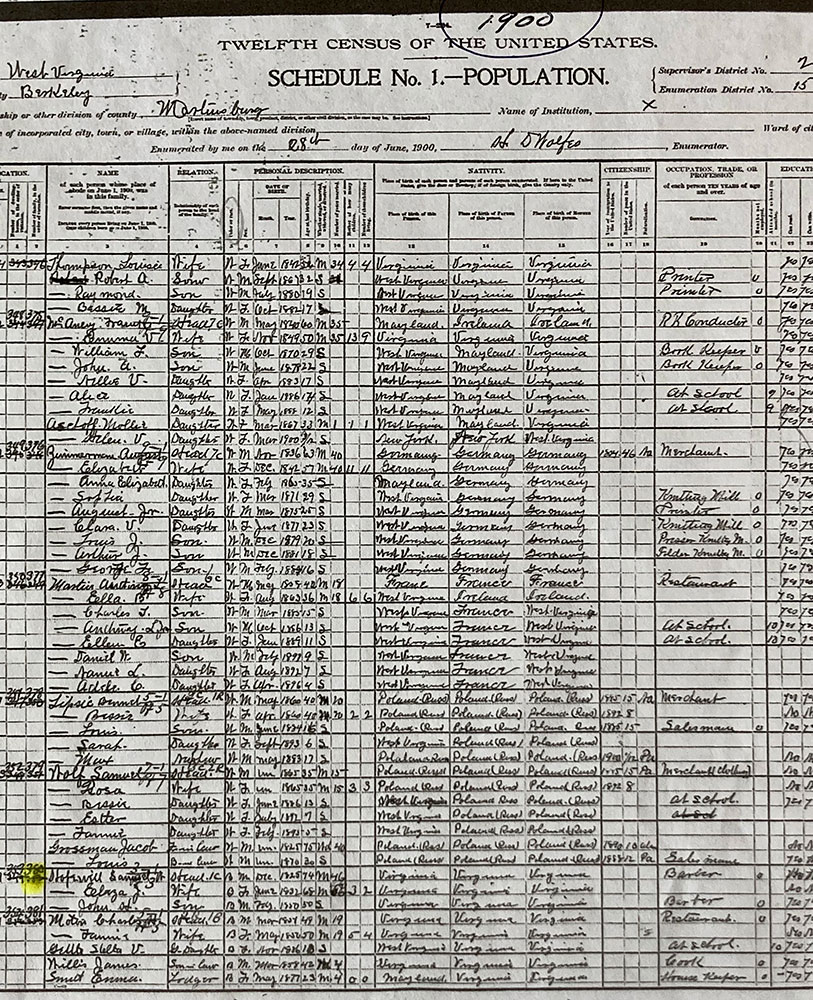

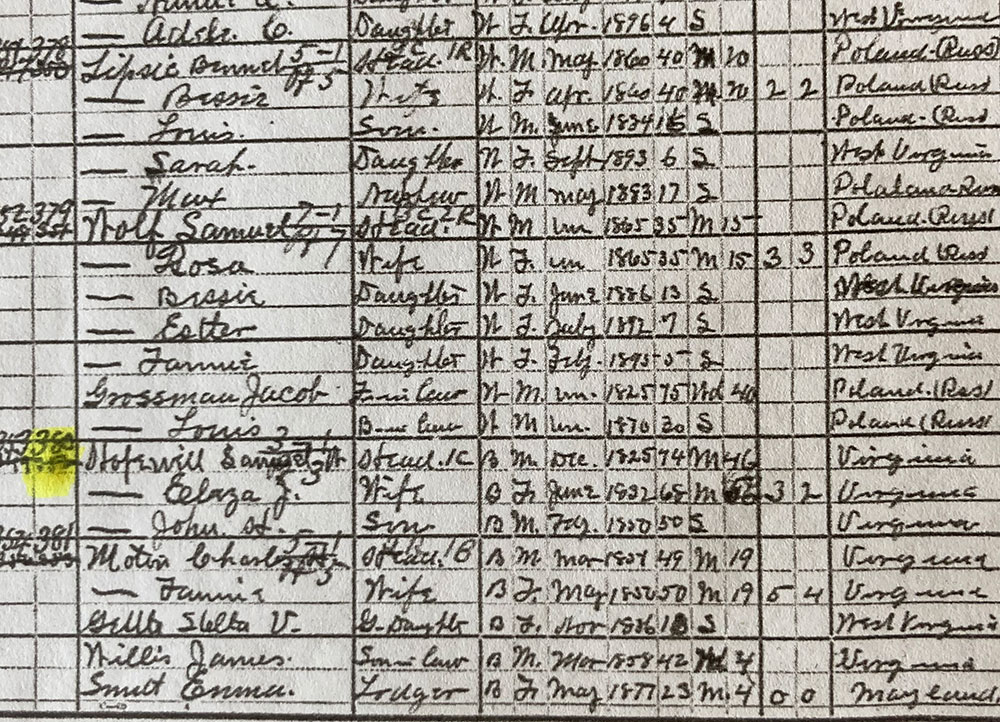

From the 1880 census we learn that Eliza and Sam’s grandchildren, John and Anna Harris, were now living with them. Two decades on, in 1900, when Eliza is 68 and Sam is 74, their son John, now aged 50, lived with them. Here is evidence that throughout their lives, Eliza and Sam remained at the center of a large extended family centered in Martinsburg.

Census Record 1900

Census Record 1900 Close-up

Beyond dispute

Eliza’s years after emancipation form a striking contrast to Belle’s. From the census records we can conjecture that Eliza had a long and comfortable life, dying in 1916 at the age of 82. She died in the town where she had spent most of her life, presumably surrounded and mourned by generations of her family. Belle, on the other hand, who began life as a pampered debutante, died a pauper at age 56, in a town hundreds of miles distant from her beloved childhood home, her only companion a devoted, far younger husband.

This aspect of Belle’s and Eliza’s story, the opposing trajectories of their lives, with Eliza’s steadily rising and Belle’s inexorably sliding downwards, is part of the historical record and beyond dispute. To me this is the dimension of their story that is most interesting and worth telling.